German Expressionism

Including a section on the German Expressionists will provide an opportunity to stimulate the children into looking at the world in ways they might never have dreamed of. This should prove beneficial in their practical art lessons.

In 1905 a group of architectural students at Dresden formed a group of artists known as 'The Bridge'. Among the group were Ernst Ludwig Kirchner, Erich Heckel and Karl Schmidt-Rottluff. They were to be joined later by other artists, notably Max Pechstein and Gabriele Munter. The original group were all interested in art and were only studying architecture to please their parents. The formation of the group followed an exhibition of the works of Van Gough held in Dresden in 1905. Van Gough was a revelation to the young German artists. His emotional involvement with the scenes he painted appealed directly to the German spirit. The group aimed to create a new utopian society the exact opposite to that which had grown out of the industrial-military ethos of the Germany under Kaiser Wilhelm II. This dream would be reflected in their art. The First World War had a great influence on the German Expressionist movement. The artists hoped and believed that it would destroy the old order, which they had felt to be so oppressive, and that a better society would arise from its ruins. Although many of them volunteered for service in the hope that they would gain fresh impressions for their art, most found that they could not bear the horrors of trench warfare.

Highlight

In 1905 a group of architectural students at Dresden formed a group of artists known as 'The Bridge'. One of the favourite themes of 'The Bridge' artists was that of man in a natural environment, unspoilt by any form of industrialisation.

One of the favourite themes of 'The Bridge' artists was that of man in a natural environment, unspoilt by any form of industrialisation. Another theme was nudes, because the artists saw their unclothed models as people carried off into a state of unspoilt bliss. Here again, these artists painted not what they saw but how they felt.

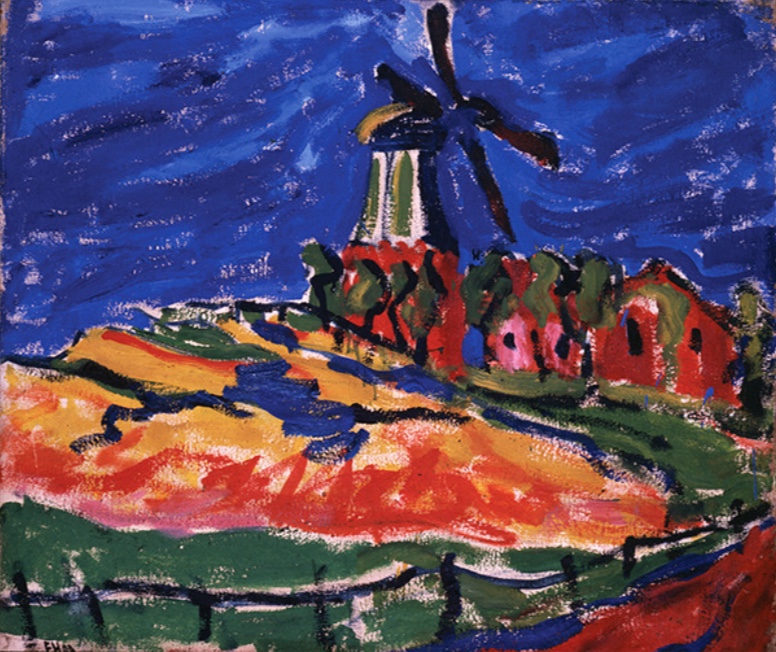

Flemish Plain. Erich Heckel, 1916. Stadtisches Museum, Abtieberg, Monchengladbah, Germany.

Heckel volunteered for service and he painted this picture during the war. Is this painting a vision of hope for a better world in which there will be peace, or on the other hand, a depiction of desolation and despair? You could begin a discussion of the painting by inviting the views of the children, supporting their opinions by reference to the picture.

There is no trace here of the ruined churned-up earth of the battlefields, rather signs of a return to green earth and cultivated fields. On the other hand, nothing remains from the war except a couple of isolated farmhouses and a few surviving tree stumps. There is a clash of orange and blue, of red and green. But most important of all is the seated figure dominating the picture as he broods over his fate, looking like the last survivor of some catastrophe. Is he a farmer whose crops have been destroyed or a refugee from the war?

Or does he see himself together with the other figure in the distance, gazing into a future of hope and peace symbolized by the blinding explosion of light already spreading its revitalizing rays over the earth? Is the painting a vision of a better future following the disappearance of the old repressive order brought about by the war.

Note all the straight diagonal lines opening out and indicating rapid movement from the centre of the picture.

Three Nudes in a Landscape. Max Pechstein, 1911. Georges Pompidou Centre, Paris.

This painting is representative of the German Expressionists' depiction of a utopian world. It shows a group of nudes, playing and talking uninhibitedly in a natural environment. Pechstein gave up spatial perspective in favour of two-dimensional areas of colour. His brushwork is spontaneous and the figures are painted sketchily in strong warm colours, their bodies outlined in black to distinguish them from the environment of which they almost form a part. Is the theme the unity of humans with nature? There are no strong contrasts of colour, everything is in perfect harmony - man and nature at one in a world of future bliss. 5This has nothing to do with the total alienation and despair of Munch or the celebration of observed contemporary life of the Impressionists. It is a statement of alienation from current norms while representing a longing for a better world.

Landscape with White Wall. Gabriele Munter 1910. Karl Ernst Osthaus Museum, Hagen, Germany.

It might be instructive for discussion purposes to compare this landscape with one by Carot or any of the Impressionists, or even Van Gough.

Munter's approach in this and in many of her works was to draw her contours on the canvas in black paint and then colour in the internal structures.

The first impression from this painting is of a flat canvas – a constant preoccupation of modern art. First of all, the background colours are just as intensive as those in the foreground, and this is due to the over-all strong colours and sharp line throughout, so no aerial perspective. Secondly, there is little or no linear perspective. Furthermore, all the forms - wall, buildings, trees and mountains are simplified into flat coloured shapes with scarcely any details of texture, modelling or tonal variations – shades of Munch here. Notice too that there are no shadows.

In reference to Vlaminck's dictum concerning his portrait, Man with a Pipe, where he stated, 'this is not a man, it is a painting', it could be said that Gabriel Munter's picture is not a landscape but a painting of a landscape. The Expressionists aimed above all to be creative and original in their approach to art. Our concern too, as teachers of art should be to open the eyes of the children to the endless variety of possibilities in making art. Let their minds be exposed to the world of art and then encouraged and allowed the freedom to invent and explore for themselves. Perhaps they could look at the landscape around them in a new way that would not involve making direct copies of nature. A practical art lesson following a discussion of Landscape with White Wall might involve children painting familiar landscapes in broad flat areas of colour, similarly with printing.

Double Portrait of S and L. 1925. Karl Schmidt-Rotluff, Museum am Ostwall, Dortmund, Germany.

Highlight

Erich Heckel was another member of the group of German Expressionists known as ‘The Bridge’ who had previously studied architecture in Dresde.

The contours of the faces are dark and angular. The colours are strong, with lots of contrasts. The artist felt sufficiently liberated from current norms to distort colour and form and thus create his own vision of the world. It is of the utmost importance that children in their practical art activities feel free likewise to explore and create. For example, children should be liberated from the notion that facial features should be painted in so-called flesh colours. Practical art lessons can include lots of work on portraits. (See section on Art in the Classroom). The inspiration can be portraits such as the one above, Man with a Pipe by Vlaminck, Portrait of Matisse by Derain and others. Erich Heckel, The Windmill of Dangast, 1909.

Erich Heckel was another member of the group of German Expressionists known as ‘The Bridge’ who had previously studied architecture in Dresden. Like the others, he was strongly influenced by Munch, Van Gough and his fellow Exprressionist, Kirchner. However, in their casual, vigorous and unfinished approach to painting, these men were determined to take the innovations of the older artists a step further.

In 1914 Heckel was drafted into the German army and served as a medical orderly throughout the war. He was vilified by the Nazis when they came to power. Later in life he was professor at the Karlsruhe Academy of Art in Berlin, i.e. from 1949 to 1956.

The Windmill of Dangast is painted in the modern ‘unfinished’ style in the strong primary colours of yellow, red and blue – yellow and red making orange and yellow and blue giving green, bearing in mind that each of those colours can be reduced slightly in intensity by the addition of a little of its complementary colour. Heckel intensifies the colours by placing complementary colours side by side, eg. orange with blue, red with green. He uses black to outline areas of colour and also to define the windmill sails against a deep blue sky. His style is characterized by the rapid gestural application of paint.

As a response, children could be asked to paint some landscapes ‘in the manner of’ Erich Heckel.

Incidentally, useful activities for the children might be in the area of researching further information through the internet about any of the artists in this project.